Two Indigenous Artists Creating Unique Products from Natural Material

TEXT / HAN CHEUNG

PHOTOS / YANG JEN PO

After a long period of marginalization, indigenous creatives are increasingly taking ownership of the traditional arts and crafts of their people, which often draw from the land and their surroundings. Many choose to present their artworks and designs in innovative and modern ways, creating unique products that preserve their people’s rich heritage by keeping it relevant.

If you visit Fenglin Township in Hualien County during April and May, you might see Liu Da-wei (indigenous name Yawi Akin) riding his motorbike around in sweltering heat to collect fallen betel-nut leaf sheaths. Although in some indigenous cultures in Taiwan these sheaths are used as food containers and hotpot vessels, they’re usually just left by the side of the road to rot.

Collecting about 100 per day, Liu is pretty much solely responsible for acquiring the 2,000 to 3,000 pieces that his design venture, Nature, requires per year. The brand’s Chinese name, “Na-qiao,” sounds like “nature,” and literally means “taking sheaths.”

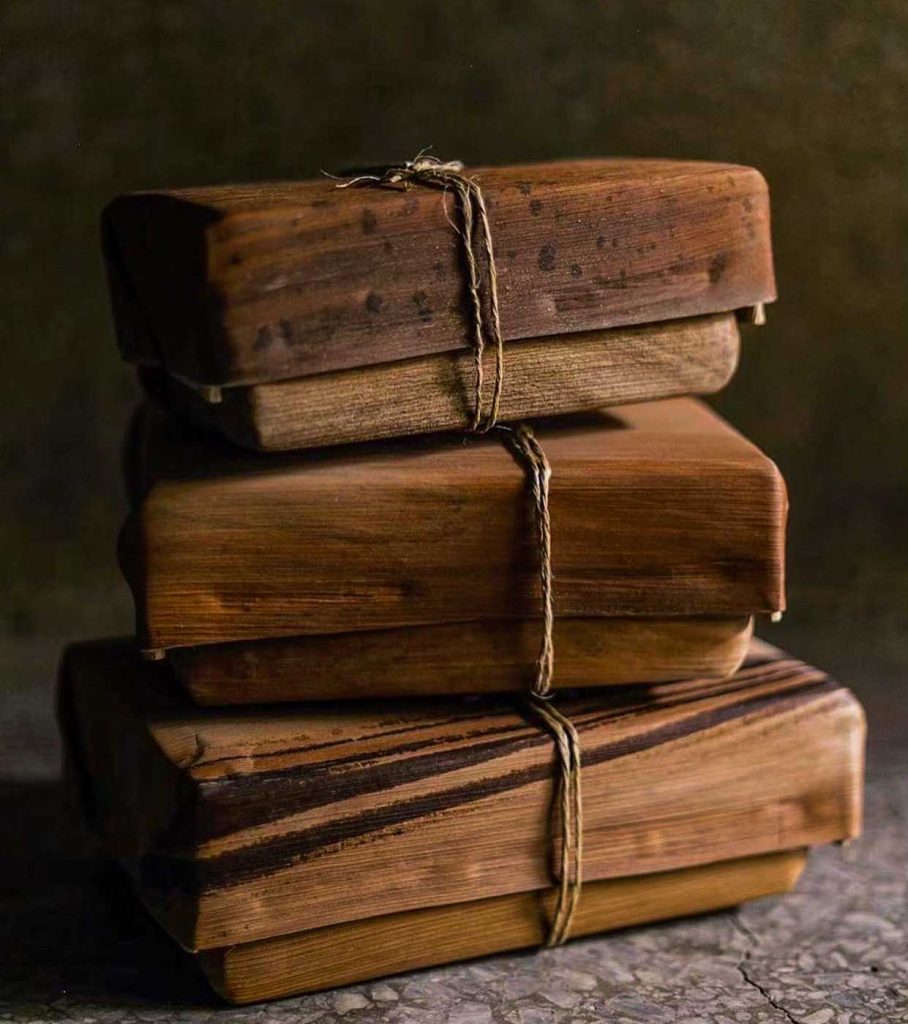

Launched in 2016, the two-person company offers simple and elegant daily-life products made from this rarely used material, created with completely natural, eco-friendly processes. Currently, the team’s focus is on boxes of different sizes and “sheath paintings,” but they also collaborate with other businesses to explore new possibilities.

Liu, a member of the Atayal tribe who majored in Russian language studies in university, grew up in the city and did not have much contact with his culture before taking a job with the central government’s Council of Indigenous Peoples. He later joined an indigenous-event planning firm, where he was introduced to the betel-nut leaf sheath for the first time through an exhibition that also showcased shell ginger and bamboo leaves.

Inspired Collaborations

“There were many people using shell ginger in our tribal villages already,” he says, “but not many using betel-nut leaf sheaths. I thought, if I didn’t want to work in an office anymore, I could try to come up with a new way to use this type of sheath.”

The betel nut is important to many indigenous cultures, but both the cultivation of the plant and the chewing of the nut generally have a negative reputation in mainstream society. In addition to finding a new use for the plant and providing new meaning for it, Liu also wanted to encourage others to use natural materials from one’s environment, as his ancestors did. Although the Atayal don’t use betel-nut sheaths, his business partner Lin Jun-yi’s (indigenous name Rahic La’om) Amis tribe does – but rarely in making products to be sold.

“We have seen more people using the sheaths in recent years,” Liu says, “and I hope that I can inspire other indigenous people to go look around their villages and see if there are any other eco-friendly creative ideas they can come up with.”

Perhaps one of the biggest challenges has been that both Nature creators are quite shy, making it difficult at first to promote their brand. They still mostly work with other designers or businesses instead of retailing directly to customers, but they try to participate in at least one design expo per year. Notable collaborations include a stone hotpot vessel-inspired light with designer Du Hsin-yu, which won a design award in Germany’s Red Dot design competition, and a room key card holder for Vivir Hotel, a boutique operation located in Jiaoxi Township, Yilan County.

“Vivir actually was interested in our boxes at first, but they were concerned that customers would think that the spots and blemishes on the sheaths were mold,” Liu says. “Instead, they thought that the material was suitable for their room key holders.”

They’ve also worked with floral artists and makers of tea ceremony ware. The latest partnership is with an embroidery design company. “I don’t know what the end product will look like yet,” Liu says with anticipation.

Processing the Sheaths

After collecting the leaves, washing and compressing them, Lin crafts them into various products. In the beginning the leaves were collected in T-shirts and shorts – but on one occasion when the duo was out gathering together they got bitten by something that caused their entire arms to swell up and go numb. At one point, they outsourced the job to locals, but the sources were unstable, causing them to run out of material by October or November. They also thought about importing sheaths from Southeast Asia, which would save a lot of time and labor, but they just couldn’t go through with it as their original intention was to strictly make use of local materials. “Otherwise, it’s really tempting,” Liu says.

Both Liu and Lin have no design or craft background – Lin studied information management – and they’re still constantly adjusting their methods and techniques as they go. Liu says that betel-nut sheath is not commonly used because its thick and hard properties are quite difficult to control. At first, he would select sheaths with a certain aesthetic, but now he says he barely does, preferring to embrace the unpredictability of each piece – although arguments between the two do arise. Sheathes differ in thickness and fiber patterns, and they also dry differently, but that is also what makes each piece unique.

Eschewing chemical softening agents, the sheaths are soaked in cold water for four hours. Hot water is faster, but they don’t even want to use gas, Liu says. The material is then folded into the desired shapes and wind-dried. No glue or other fastening materials are needed to keep the folded boxes together, as the material retains its shape after hardening.

“To get the sheaths flat and even, we have to be very attentive throughout the process,” Liu says. “It’s not too complicated, but it requires a lot of patience and time.”

Although the Amis traditionally used these sheaths to fashion food containers, Liu doesn’t recommend customers do so with their boxes, as they may lose their shape and unfold with heat and moisture. They considered adding a protective film to the box, but again decided to stick to the idea of only using sheaths in their most natural state. “Some people know how to take care of natural materials, and they’ve shared photos of themselves using them as bento boxes,” he says.

Their light fixtures are unfortunately currently unavailable, as they’ve had trouble finding a metalworker who is up for such a delicate task and raw material prices have been soaring of late.

All in all, Liu hopes that the story of Nature can reach each customer, who, through this unique material, can gain a new perspective on society, culture and the environment.

Nature

(拿鞘)

Add: No. 81, Zhongmei Rd., Fenglin Township, Hualien County

(花蓮縣鳳林鎮中美路81號)

Website: www.nihaonature.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/Naturewor