Embracing Everything Else that Southern Pingtung Has to Offer

TEXT | AMI BARNES

PHOTOS | ALAN WEN, VISION

Pingtung has a reputation for being a beautiful, breezy, tropical beach-type of destination, and the further south you head, the more strongly that impression holds. And while it’s true that Taiwan’s southernmost county is hugged by miles and miles of sandy coastlines, beaches are far from the only reason to pay the region a visit.

Southern Pingtung, with its perpetually warm weather and laidback lifestyle, is a prime place to escape the dreich and dreary Taipei winters. The region’s climate and geology have gifted it with impressive biodiversity – vast tracts of national parkland drape themselves over sun-soaked hills, with coral limestone caves, tropical forests, and clear mountain streams all waiting to be explored. The land’s geopolitical and cultural history also has much to bring to the table. Sleepy towns with half-forgotten past lives as indigenous hunting villages and regional maritime hubs pepper the Hengchun Peninsula, now home to storied temples and markets with eateries serving up much-loved traditional dishes.

Content

Shizi Township

Shuangliu National Forest Recreation Area

The Shuangliu National Forest Recreation Area is one of those places that seems to luxuriate under the weighted blanket of a sullen sky. On grey days with the clouds pressing in, moody mists accentuate the mineral-tinted waters and damp air polishes the leaves to a bright glossy sheen – even the trees seem to revel in the atmosphere, knitting together in conspiracy to keep outside influences at bay. It feels cut off from the world in a good way.

One of two national forest recreation areas located in Taiwan’s southernmost county (the other is Kenting National Forest Recreation Area, more on which later), it occupies a sheltered valley right at the tailbone tip of the Central Mountain Range, an area of old indigenous hunting grounds. Shuangliu means “twin streams” – a reference to the fact that two tributaries of the Fenggang Creek tumble and dash to their confluence here.

Speaking of creeks, Shuangliu’s waterways make their presence felt. Wherever you go within the confines of the park, you are accompanied by the sound of H2O – at times, a gentle whisper or gurgle, at others, the deafening roar of a full-throttle waterfall. As a result, the air feels gloriously fresh – post-thunderstorm-summer-afternoon fresh. The swish and flash of tiny silvery fish busy the pristine waters of deeper pools. Nearby signs say the Taiwan banded barb, Pingtung candida, Formosan striped dace, Pingtung horse mouth, giant spotted eel, and monk goby are all present in large numbers. Meanwhile, in the shallower channels that run beside the walkways, Rumsfeld stream crabs and Huang Ze gray crabs can be spotted filter-feeding and guarding the entrances to their burrows.

These healthy rivers form the foundations of a vibrant and diverse forest biome. Damselflies and minuscule hunting spiders stake out the fringes of waterways, and the surrounding greenery is studded with flashes of color from trailing daisies, Taiwan toad lilies, and budding hibiscus trees. The air is permeated by a pleasant earthy aroma of humus and woody ferns, and wandering along the trails I encountered perfumed top notes of white ginger lily and the sweet, almost fruity whiff of monkey poop (somehow alarmingly inoffensive as part of the larger olfactory landscape).

Aside from humans, monkeys are the most commonly seen larger animal in Shuangliu. Smelled before heard, and heard before seen, you’ll likely spot a troupe stripping the upper branches of their sweetest leaves and giving off harsh alarm barks to any foolish human that dares to stare too long. (The monkeys here are shy, but normal rules apply: don’t get your food out in front of them, and don’t make eye contact.) The park is also home to mongooses, pangolins, muntjac deer, flying squirrels, several species of snake, civets, tree frogs, fireflies, and charismatic endemic avians such as Formosan blue magpies and Swinhoe’s pheasants. If you’re lucky you’ll spot one or two of these on any given day.

The amount of flexibility in your schedule – and your degree of eagerness to get your money’s worth out of the NT$100 entry fee – will dictate how best to allocate your time. All of the park’s four trails could feasibly be covered in a single day by anyone in possession of a comfortable pair of shoes plus a willingness to start early and wear themselves out. However, for a half-day excursion, your best bet is to take the Waterfall Trail and then head back via the Mountainside Trail.

The Waterfall Trail is the easiest of the four by quite a measure. Indeed, the first 2km stretch is an almost entirely step-free amble along a broad gravel track that winds its way gently upwards shadowing each twist and turn of the river. The ease of walking leaves your mind free to focus on other things, like admiring the mosaic of lichens adorning tree trunks or puzzling over who might be occupying the various bird and bat boxes. Roughly a third of the way in, stepping stones ford the Fenggang Creek. The stones are stable and flat, and the gaps between them are small enough for even a toddler to cross with a little assistance, but of course, there’s always the option to remove your shoes and paddle across the ankle-deep crossings. This is probably the park’s main draw for lots of visitors, and judging by the fact that the crowd beyond this point was much smaller during my recent visit, I suspect a fair few folks only ever make it this far.

A rest area with bathrooms and a viewing platform sits at the 2km mark, and then a short way beyond that, the difficulty level kicks up a notch. Zigzagging steps and interconnecting dirt trails lead up and then down again as the rumble of the waterfall draws ever closer. It took our party 90 minutes to walk from the park’s visitor center to the wooden platform overlooking Shuangliu Waterfall. Water leaps slantwise over a rocky precipice before giving in to the tug of gravity about a third of the way down a 25m drop, resulting in a splendid white fan. On our visit, the cascade was so energetic that a fine mist carried on the breeze to where we were standing.

If you’re still full of beans on the way back, you can detour to explore the Mountainside Trail. This runs parallel to – and about 50m above – the Waterfall Trail. It’s marginally harder on account of the ascent, but on the plus side, this means that it’s also quieter. Part-way along the trail, a suspension bridge hangs across one of the aforementioned tributaries, allowing you to enjoy a bird’s-eye view of other hikers taking the easy route.

Completing the park’s full complement of trails are the Banyan Tree Trail and Mount Maozi Trail. The former is a 1.9km climb through dense woodland that’s rated “moderate” by park authorities. Thick blue-green grass carpets the forest floor, and there’s a high chance of spotting sleek-coated muntjacs picking their way through the shadows. It starts next to the ruins of an old Paiwan dwelling near the visitor center and connects to the Waterfall Trail where that trail crosses the creek. The fourth and final trail is also the park’s toughest. Striking out from immediately beside the park’s entrance, a round trip is about 5.7km and takes around 3 hours to complete. On a clear day, the summit offers views of both the Taiwan Strait to the west and the Pacific Ocean to the east.

As far as practicalities go, Shuangliu is best accessed by private car by following Provincial Highway 9. It’s also worth noting that although the park has water dispensers, it doesn’t sell any food or drink, so it would be wise to purchase provisions from the convenience store just outside the main gate before obtaining your tickets.

Shuangliu National Forest Recreation Area

(雙流國家森林遊樂區)

Add: No. 23, Ln. 2, Danlu, Shizi Township, Pingtung County

(屏東縣獅子鄉丹路2巷23號)

Tel: (08) 870-1393

Website: recreation.forest.gov.tw

Family and wheelchair friendly

The Waterfall Trail, up to the creek crossing, is gentle and easy to navigate, making it suitable for families with young children, the elderly, and wheelchair users.

Checheng Township

National Museum of Marine Biology & Aquarium

The National Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium (NMMBA) is one of the primary draws of Checheng Township. This sprawling attraction has been providing schools and travelers with a place for education, entertainment, and blessed air conditioning since it opened in 2000.

Its exhibits are split among three permanent collections. Waters of Taiwan follows the route traced by a raindrop as it descends through Taiwan’s aquatic ecosystems – young alpine streams, reservoirs, coastal aquaculture, estuaries, mangroves, and finally out to sea. The journey concludes with the Open Ocean tank – the largest of the aquarium’s exhibit areas – where sharks and rays glide serenely, shoals of sea bream and bonitos knot around each other, and giant solitary groupers do … well, nothing much.

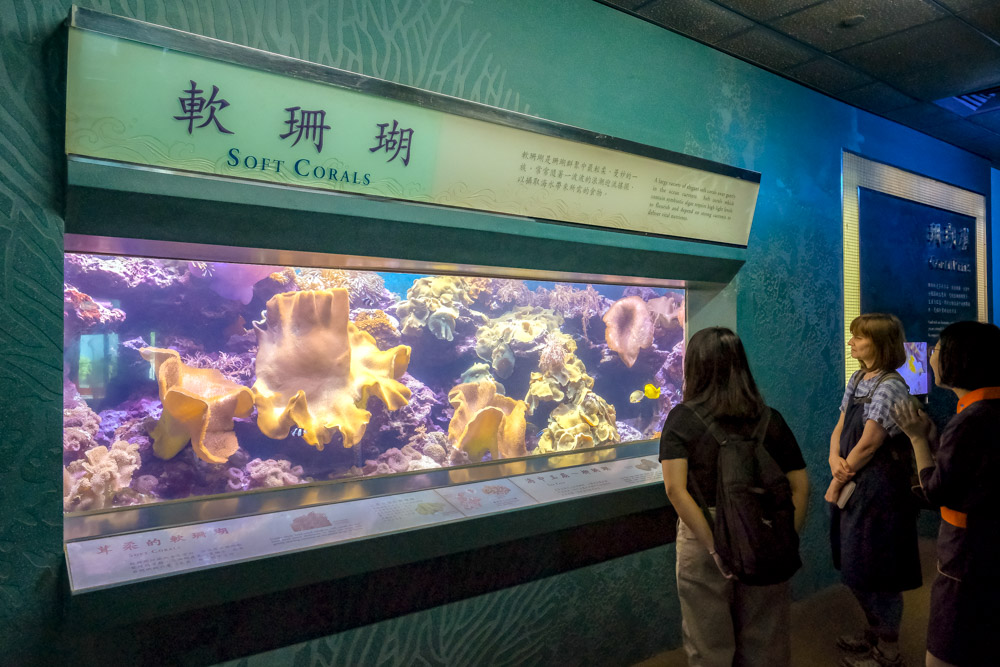

Coral Kingdom unveils the weird and wonderful world of corals. Here, the star of the show is a 1.5-million-gallon tank constructed around a shipwreck. Underwater tunnels crisscross the space, offering you the chance to observe how a reef forms as corals colonize different areas of a sunken ship.

The third collection, Waters of the World, is housed in a separate building accessed by a short walk across a seaward-facing terrace. Exhibits here cover all manner of aquatic life from around the planet, from the visually engrossing spectacle of a giant kelp forest to harbor seals and cute penguins.

All three collections host feeding shows at different times throughout the day. In Waters of Taiwan, we watched as the be-wetsuited diver’s arrival was preceded by an eerie disappearance of all the fish – they’d got wind of his presence before we had and were following him, out of sight, as if he were the Pied Piper of the deep. As he neared the center of the 16m-wide window, he was mobbed by greedy rays eager to get their jaws around his goodies. We didn’t manage to catch any of the other feeding demonstrations, but both Coral Kingdom and Waters of the World have fish feeding shows, and the latter also gives visitors the chance to watch its seals, puffins, and penguins enjoying a snack. (Schedules for feeding times can be found on the NMMBA website.)

For those who have already seen their fair share of aquariums, the NMMBA still has plenty to offer. In addition to the front-of-house displays, the facility also runs behind-the-scenes tours and even overnight stays. During our visit we took abridged versions of two behind-the-scenes tours (they usually last 50 minutes and cost an extra NT$250 per guest).

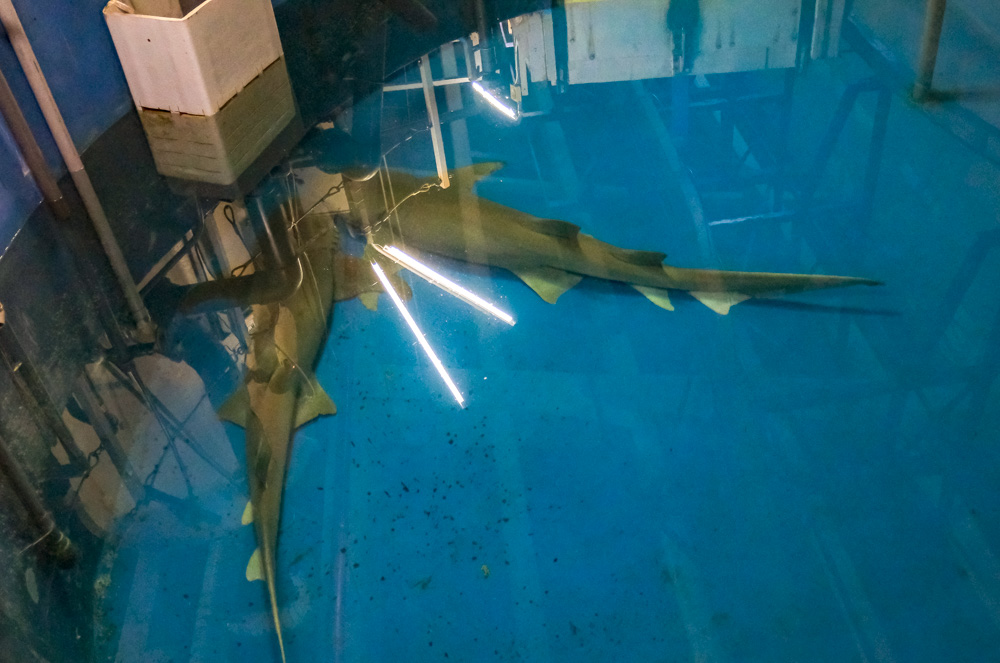

The first things that hit you when you walk into the “backstage” areas are the saltwater smell and the warmth (the moisture and salt would wreak havoc with an air-conditioning system, so there isn’t one). We saw acclimatization tanks where schools of young fish are schooled – literally – in the art of ignoring gawping humans; we watched an employee feed fish from a mechanized platform; and we learned about the different types of frozen fish the aquarium’s denizens enjoy. For me, the highlight of this behind-the-scenes experience was finding out that nurse sharks have a reputation for being – in the words of our guide – ‘salary thieves.’ These docile beasts live rather sedentary lives, spending the majority of their time sleeping in the hidden examination tank (where animals are brought if they need medical attention) and eating fish given to them. They rarely ‘go to work,’ i.e. swimming in front of visitors.

These behind-the-scenes tours run twice daily, and can be booked on-site. However, guests requiring English-speaking guides are advised to call ahead to ensure their needs can be accommodated.

National Museum of Marine Biology & Aquarium

(國立海洋生物博物館)

Add: No. 2, Houwan Rd., Houwan Village, Checheng Township, Pingtung County

(屏東縣車城鄉後灣村後灣路2號)

Tel: (08) 882-5678

Website: www.nmmba.gov.tw

Family and wheelchair friendly

The museum/aquarium provides accessible routes and facilities, making it easy for visitors with disabilities, families with young children, and the elderly to enjoy the exhibits.

Checheng Town

In the 1600s, a legion of Fujianese immigrants journeyed across the Taiwan Strait looking for a better life. Many arrived in what is today Tainan’s Anping District before dispersing north or south to various other coastal settlements, with a sizeable portion of the southern drifters settling in the area that is now known as the town of Checheng, the site of our next stop.

Life was hard. The farmland wasn’t what they were used to, and there were clashes with the indigenous groups who had lived there first. Seeking succor from the old country’s gods, they built a small shrine dedicated to Tudi Gong, a “God of the Land” for a specific area, and a bringer of prosperity to righteous supplicants.

With time, Checheng flourished. The grateful residents used their wealth to undertake expansion projects, and when the most recent was completed in 1987, Fu’an Temple became the largest Tudi Gong temple in Taiwan – a crown it still bears. An adjacent market catering to hungry pilgrims sprang up, as did accommodation geared towards hosting large parties of religious travelers. The temple also garnered media fascination thanks to the odd way its furnace sucks in spirit money one leaf at a time, as if counting them. The phenomenon is an example of the chimney effect and has resulted in the furnace being nicknamed “the gods’ money counting machine.”

We visited on a spiritually insignificant Tuesday, nevertheless finding the temple courtyard abuzz with activity. A small procession had just finished – the scent of spent firecrackers lingered in the air, and a spirit medium bearing signs of self-mortification blessed a car as it was being loaded up with a touring deity. Inside, it is quite unlike anything I’ve seen in other Tudi Gong temples – the main hall soars four floors up, giving a majestic sense of scale, every surface covered in intricate decorative details. Incense and white champaca perfumed the air, and a steady stream of people flowed through bearing offerings and requests.

Checheng’s other claim to fame is its glut of dessert shops specializing in treats made with sweetened mung beans. In Mandarin, the dish is called “mung beans and garlic,” but the “garlic” is, in fact, dehusked beans that have the appearance of chopped garlic. Over a dozen Checheng vendors sell their own versions of this treat, but we settled on Huang’s Sweet Mung Bean Soup and ordered two signature bowls – one warm, one iced. I confess it took me nearly a decade to make my peace with sweet beans (the result of an unfortunate misunderstanding involving what I thought was a chocolate chip ice lolly during my first week in Asia), but I can finally say that I get it. Melt-in-the-mouth beans are combined with glistening strands of silver needle noodles and chewy tapioca balls, and the whole dish is tied together with a viscous soup lightly sweetened with dried longan and brown sugar. It’s a textural party. And at just NT$50 a bowl, it’s a great energy boost to fuel further travels.

If, like former me, you’re not on board with the whole sweet bean thing, there are savory options in the food market behind Fu’an Temple. The place is crowded with stalls selling cheap and cheerful traditional local fare, and my companions had their stomachs set on lunch at Fubo Duck Rice – identifiable by its flower-patterned tables. By 1pm, this restaurant’s eponymous specialty had sold out, so they contented themselves with swordfish balls in a radish-infused broth, duck meat noodles, and a shrimp omelet slathered with a sweet, tangy sauce – by all accounts, a wholly satisfying spread.

Hengchun Township

Kenting National Forest Recreation Area

Sitting around 300m above sea level, Kenting National Forest Recreation Area (KNFRA) was once underwater – as attested to by the park’s distinctive coral limestone rocks. In fact, the uplift persists to this day, albeit at the imperceptibly genteel pace of 2.5-5mm per year. Adding to the park’s interesting credentials is evidence of a prehistoric culture – patterned pottery, farming implements, burial cists – unearthed during the early period of Japanese colonial rule (1895~1945) that saw authorities conducting extensive surveys of their new acquisition.

Later, the Forestry Department of the Governor’s Office in Taiwan established a botanical research institute on the site. The facility – Hengchun Forestry Experiment Branch Guizijiao Test Site – was tasked with assessing which plants were well-suited to widescale cultivation and exploitation. Over 500 species were put through their paces, with different areas set aside for cultivating native, tropical, and alpine plants. After the end of World War II, the incoming Nationalist government maintained the park as a research center for a long period before opening it to the public in 1968.

Visitors can pick their own exploration route, but there are two recommended itineraries: the Plant Walk and the Geology Exploration. The former is a gentle 1-2hr stroll along well-surfaced trails – it’s smooth enough to be pushchair-friendly, but it may be too steep for wheelchair users in places. Much of the original collection can still be observed along the way, split up into zones by family (palms, legumes), by habitat and origin (wetlands, Orchid Island), or by usefulness (plants used in folk medicine).

The second route requires a further hour or two and a little more legwork. Steps and paved trails lead deep into a forest dominated by laurels, mulberries, and bishop wood trees. On a previous visit, I observed sika deer peering out from the undergrowth, and on this occasion, monkeys. We found ourselves weaving through the prop roots of strangler figs, past lookout spots with distant ocean views, and descending into subterranean chambers full of oddly shaped stalactites.

The porous rocks of the cave walls seem to enforce a respectful hush by sucking all the sound out of the air, and if you visit on a quiet day, you can listen to the plink-plinking of water – each drop adding infinitesimally to the cave’s calcified structures. The park authorities have done a great job of making these caves fun to explore. They’re artfully lit and generally spacious enough to not trigger claustrophobic thoughts – the Fairy Cave in particular is a tame introduction to spelunking.

Getting to the recreation area is pretty straightforward. If driving, turn off Provincial Highway 26 through the large KNFRA arch and continue until you reach the parking lot in front of the ticket booth. The park can also be reached by the 8248 bus from Hengchun Bus Station in the town of Hengchun (it stops at the arch too, which is at the edge of tourist-popular Kenting town), but be aware that services are limited.

Kenting National Forest Recreation Area

(墾丁國家森林遊樂區)

Add: No. 201, Gongyuan Rd., Kending Borough, Hengchun Township, Pingtung County

(屏東縣恆春鎮墾丁里公園路201號)

Tel: (08) 886 1211

Website: recreation.forest.gov.tw

Family and wheelchair friendly

The forest recreation area features several gentle, easy-to-navigate trails (with wheelchair-friendly bathrooms), perfect for families with young children, the elderly, and wheelchair users.