Reveling in the Gentle Loveliness of Miaoli’s Shitan and Nanzhuang Townships

TEXT | AMI BARNES

PHOTOS | RAY CHANG

Bounded by Hsinchu County on the north, Taichung on the south, the Taiwan Strait to the west, and the towering central mountains on the east, Miaoli is a quiet, primarily rural county. Home to storied trails, seasonal blossoms, fruit orchards, hot springs, and cultural cross-pollination between its majority Han and minority Hakka and indigenous residents, even at its most urban it feels a far cry from the clamor of Taiwan’s big modern cities — and that’s exactly why you should visit.

Despite the attractions mentioned above, Miaoli usually flies under the tourism radar. Taken individually, its various draws seem pleasant, albeit something of a hard sell for travelers short on time. However, when considered cumulatively, they create an ideal base for slow travel – less whistle-stop highlights touring, more marinating in the landscape, allowing its cuisine to nourish, its culture to delight, and its trails to unfold beneath your feet. Indeed, the region has so much to offer for visitors who want to sink into their surroundings that you’ll soon find yourself needing to narrow down the options. Shitan and Nanzhuang – the two townships being spotlighted here – present more than enough of Miaoli’s unhurried loveliness to capture your attention.

Content

Shitan Township

Raknus Selu Trail

Nothing epitomizes slow travel more than making your way from place to place on foot, as is the goal for those taking on the Raknus Selu Trail. Snaking its way down from rural Taoyuan, through Hsinchu, Miaoli, and over the border into Taichung, this long-distance walking route is one of three national greenways threading through Taiwan’s verdant hills. The Raknus Selu Trail traverses land home to both Hakka and two of Taiwan’s 16 officially recognized indigenous groups, the Saisiyat and the Atayal, and its name is drawn from this blend of cultures. “Raknus” is the Atayal name for camphor trees (once found in abundance along the way), while “Selu” means “small roads” in Hakka, and much like the name, the route itself is a patchwork stitched together from historic trails, farm tracks, rural backroads, and stops in wayside towns.

With the main trail coming in at around 220km, a seasoned thru-hiker might expect to complete the route in a little over a week, but in reality, it deserves about a fortnight. This trail has been conceived as a cultural journey as much as a physical feat, so to crack through a crushing 30km a day would entirely miss the point. This is something I can speak to from intimate personal experience, since I’ve recently completed a hike of the entire route broken up into several 2- or 3-day sections, falling totally in love with the region’s mellow appeal along the way.

For those seeking a shorter taste of the trail, several sections have been singled out as being enjoyable and especially representative of the region’s scenery, one of which is the Mingfeng Ancient Trail. In its original iteration, this section was used by hunters from the Saisiyat tribe before later becoming a trading route between the Shitan and Touwu areas. These days the path is popular with weekend hikers, and since 2019 it has also shouldered a diplomatic role after becoming the first internationally twinned trail in Taiwan, in a sister-trail relationship formed with the Jeju Olle Trail in South Korea.

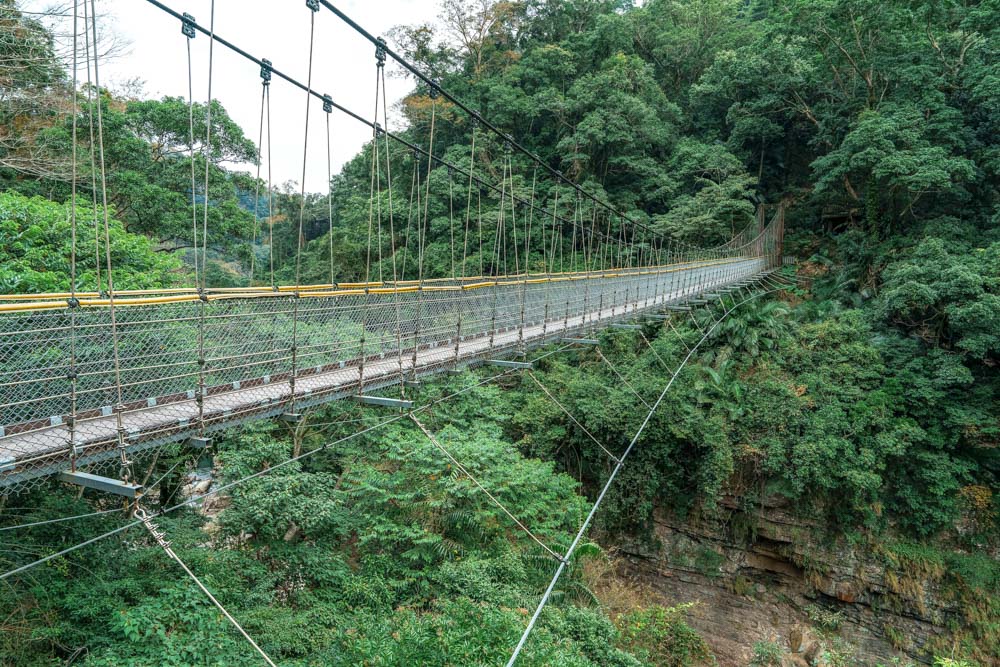

The walk starts close to Shitan Yimin Temple in Xindian Village, not far from Shitan Xindian Old Street (see page 5). From the temple’s carpark head to Xindian Creek, and you’ll soon find yourself standing in front of the Xinfeng Suspension Bridge. To one side, you can find one of the trail’s 22 passport stamps in the backyard of the Little Blue House, a community classroom that doubles as one of the Raknus Selu’s six workstations. (The second-generation passports have just been published and can be purchased online at www.tmitrail.org.tw/publication/2015.)

After crossing the bridge, yellow Raknus Selu signage leads you through an oil-seed camellia orchard before heading uphill into a lively mixed forest. Mature camphor trees and whispering bamboo preside over a lush understory full of ferns, and from April to May each year the old stone steps of the trail are carpeted with white tung flowers and tiny yellow acacia pom poms.

Along the route, there are a few points where walkers can pause to catch their breath and enjoy the scenery. The most interesting of these is Lovers’ Valley. Previously a boundary between indigenous and Han peoples’ lands, it saw occasional bloody scuffles, but standing in the shady hollow now, you’d never guess it was the site of such unrest. The new name was selected in part to erase the memory of this painful history, and also because two small creeks merge here like lovers coming together. Further up, the trail eventually brings you to Yundong Temple, where you can fill up your water bottle and greet the resident gods before heading back down the same way.

Xindian Village

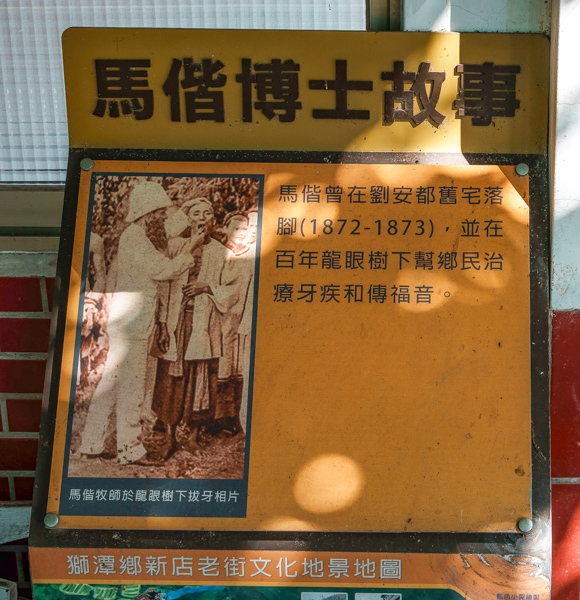

Seen on a map, Shitan Township forms a lopsided skinny rectangle encompassing land on both sides of north-south Provincial Highway 3. Xindian Village sits at the center, a sleepy settlement home to Shitan Xindian Old Street and a population just shy of 1,000. You should get some sense of the kind of place it is when I say that one of the village’s premier sightseeing spots is the Century-Old Longan Tree, which once provided shade to Dr. George Leslie Mackay as he wielded his dental forceps.

Mackay was a Canadian Presbyterian missionary, doctor, and beloved adopted son of Taiwan who arrived on the island in 1871, married a local and gained proficiency in Mandarin and Hokkien. He became known for walking from town to town pulling teeth and proselytizing, and in one diary entry, Mackay noted that between them, he and his local trainees regularly extracted more than 100 teeth within an hour of setting up an open-air treatment station. Mackay’s longan can be found up a painted side lane, tucked into the courtyard of a private residence. Beside it, a board bears an age-faded photo of the bearded, pith-helmeted practitioner treating a patient on one of his travels through the Taiwanese countryside.

Wandering up its little side lanes is the best way to explore Xindian Village, and there’s no need to worry about getting lost – there are only about ten streets. On a recent Travel in Taiwan exploratory visit, near Mackay’s tree we came across the stream-fed Xindian Village Clothes Washing Pool, where villagers used to gather to wash clothes and have a good gossip. Previously common throughout Taiwan, the arrival of modern washing machines rendered these village hubs obsolete, but a few remain in active use, especially in areas where there are large populations of the famously hardy and frugal Hakka folk.

Another road leads to the village’s religious sites. Temples dedicated to Tudi Gong – God of the Land – are commonly seen in Taiwan, but in Hakka areas, this deity goes by the name Bo Gong, and Xindian has two such places of worship. The one at the northern end of the Old Street is named Pig Skin Bo Gong Temple (referencing a Japanese leather-tanning station set up here during World War II), while the second sits a little further back, shaded by a towering Formosan sweetgum. Less than 100m up the street is the Shitan Presbyterian Church. The current structure dates back to the late 1990s, but the village’s congregation was established over 150 years ago by Dr. Mackay.

Another 100m will take you to Shinong Xiaopu, a shop run by the local farmers’ association in a converted rice mill. The mill equipment has been preserved in situ, and colorful illustrations detail the rice-milling process, while the adjacent room is given over to shelves full of local produce. For bold snackers, there are many potential souvenirs: preserved peppers, pickled cucumbers, fermented bamboo shoots, sour-plum candy, and freeze-dried mushrooms.

Shinong Xiaopu | 獅農小舖

Add: No. 125, Neighborhood 11, Xindian Village, Shitan Township, Miaoli County

(苗栗縣獅潭鄉新店村11鄰125號)

Tel: (03) 793-1340

Hours: Tue-Fri 8am-4:30pm; Sat-Sun 9am-4:30pm

Website: shihtan.naffic.org.tw (Shitan Farmers’ Association; Chinese)

If you need something more substantial, however, Shianshan Shiantsau is a better bet. This restaurant is located on the Old Street, and its menu centers around a single ingredient: xiancao or mesona – a mint relative often featured in herbal drinks and sweets. In addition to the standard teas and grass jelly desserts, Shianshan Shiantsau has found ways to incorporate mesona into a whole range of Hakka-inspired fare. The chewy flat rice noodles and pork dumplings – both tinted ashy-brown by the herb – mesona-infused chicken soup, and deep-fried cubes of grass jelly (the restaurant’s signature dish) are bound to satisfy even the hungriest customer.

Shianshan Shiantsau | 仙山仙草

Add: No. 62, Xindian Village, Shitan Township, Miaoli County

(苗栗縣獅潭鄉新店村62號)

Tel: (03) 793-2318

FB: facebook.com/shianshan.shiantsau

Nanzhuang Township

Penglai Village

From Xindian Village, County Highway 124 has the form of a wobbly check mark, heading southeast past lofty Xianshan Lingdong Temple before bouncing back to cut northeast towards the town of Nanzhuang. This northbound portion is remote and hilly, and the road mostly hews close to the course of the Penglai Creek. Every other property seems to be a campsite or homestay, and here and there, the density of houses increases a smidge as you pass through a hamlet or tribal village, among them Penglai Village. Known as Ray’in in the language of its majority Saisiyat indigenous inhabitants, this village is little more than a straggly string of houses, a police station, a school, and a couple of stores, but what makes it visit-worthy is the Penglai Creek Fish Watching Trail, a scenic 1.5km riverside stroll easy enough even for infrequent hikers.

The Penglai Creek story is one I’ve heard repeated in various communities around Taiwan. For a while in recent times, technological innovations in fishing practices outstripped advancements in ecological awareness, and the delicate balance of creek life was thrown into disarray. Realizing this, the villagers banded together to clean and protect the waterway and to educate others on the importance of conservation. Their efforts were successful, and a fish-watching trail was established so that people could come to appreciate the region’s natural bounty with their eyes and ears instead of their bellies.

Two trailheads offer access to the waterside path. One is located by Shangzhuang bus stop, at the north end of the village – it has a designated car park and (on weekends) a few food vendors. The other can be found next to Qixing Temple, and although there is no car park, roadside parking is available. Most people choose to do a there-and-back walk from the north trailhead, but you could easily turn it into a loop by walking back up (or down the road), and whichever option you choose, it’s unlikely to take longer than 90 minutes.

Trailside information boards offer brief introductions to the creek and its denizens – many of them written from the perspective of Xiaohua, a cartoonified shoveljaw carp. The waters are full of fish, which are watched over by hungry herons, and on the far bank, we observed a troop of monkeys stripping leaves off a tree and a silent muntjac slipping back into the undergrowth after stealing a drink. Midweek, it was just us and the animals – deliciously quiet.

We made a clockwise loop, starting at Qixing Temple and then walking back along the road, finishing our outing with a stop at Forest Corner, a small village-run store. In operation since 2018, it is the fruit of a joint initiative between the Miaoli branch of the Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency (formerly the Forestry Bureau) and Penglai’s residents. The initiative involved providing education in subjects such as beekeeping and mushroom horticulture and granted villagers extra rights to earn a living through sustainable stewardship of their ancestral lands. Success was anything but guaranteed. In times past, the two parties had a fractious relationship, so to get the partnership off to an auspicious start, representatives from both groups held a ceremony to appease the spirits of aggrieved Saisiyat ancestors with skewered meats and millet wine.

It seems the offerings were deemed sufficient because if you visit now you’ll find the display spaces full of beautifully presented honey, fresh eggs, aromatic botanicals, and dried mushrooms – all locally grown. There are also tables out back where you can sit down for a coffee.

Forest Corner | 森林小站

Add: No. 93-1, Hongmao Bldg, Neighborhood 7, Penglai Village, Shitan Township, Miaoli County

(苗栗縣南庄鄉蓬萊村7鄰紅毛館93-1號)

Tel: (02) 2773-8913

Hours: Mon-Fri 9:30am-6:30pm; Sat-Sun 9am-2pm

FB: facebook.com/SaySiyat.pakaSan.Satoyam

Central Nanzhuang

If you’re relying on public transport, Nanzhuang Old Street is one of the easiest places to get to for a little taste of Miaoli’s rural character. A direct bus from Zhunan Railway Station (the 5806) in Zhunan, a town near Hsinchu City, takes a little over an hour to whisk you out of the urbanized flatlands into the hilly countryside. Similar to Shitan, Nanzhuang occupies the interesting position of straddling the boundary between Hakka and indigenous peoples, although, unlike predominantly Hakka Shitan, Nanzhuang has sizeable populations of both groups.

The southern end of Nanzhuang’s Osmanthus Alley makes as good a place as any to commence an exploration of the town. Here you’ll find a clothes-washing pool – part of a glorified irrigation canal – which has been spruced up with a splash of colorful paintwork. Bright lights entice you into a lane that is just wide enough for three people to walk abreast, both sides lined by shopfronts, and proprietors tempt purchases by offering samples of their wares to each “handsome man” or “beautiful woman” who passes by.

Osmanthus-flavored treats make up a good portion of the souvenirs on offer. The area’s osmanthus wine is much loved, as is the osmanthus-scented honey, but you’ll also find the floral flavor incorporated into all sorts of other snacks such as osmanthus ice cream, tangyuan (glutinous rice balls), and sausages. We tried osmanthus egg rolls (with a lightly detectable osmanthus taste) from Jingguang Osmanthus Handmade Egg Rolls, where you can watch a machine press dough into thin sheets ready to be curled around metal cylinders.

Hakka food is the second key pillar of Nanzhuang’s culinary landscape, and – not wanting to miss an opportunity to try some – we stopped by Mama Yang’s Hakka Rice Specialties on Zhongzheng Road, parallel to Osmanthus Alley, to get our hands on a couple of cold rice cakes and Hakka dumplings (also called “pig cage buns” because they resemble wicker pig cages). The latter are seasoned shredded meat and vegetables encased in a rice-flour skin, while the former are essentially chewy blocks of rice jelly with a subtle brown-sugar aroma – the presentation might look a little different, but texturally they’re not dissimilar to gummy candies.

Of course, as well as sampling the local cuisine, make sure to explore some of the town’s other sights. At the top (end of Osmanthus Alley, just past Yongchang Temple, is the reconstructed form of the Nanzhuang Old Post Office. First built in 1900 as the Japanese colonial government began expanding coal and camphor extraction operations in the area, the structure was damaged in a 1935 earthquake before being rebuilt, thereafter serving as the town’s post office until 1996.

And should you find you’ve had enough of the crowds, note that Nanzhuang is home to three “old streets,” and only Nanzhuang Old Street itself seems to have any tourists. Admittedly, that’s because the other two have few businesses to bring in foot traffic, but it’s still worth taking a quick little wander. Shisanjian Old Street can be found on a short riverside stretch of Zhongshan Road – the buildings are a real hodge-podge of eras, with wood-paneled and brick buildings interspersed among the more common concrete façades, while the third old street, Nanjiang Old Street, can be accessed by walking across the springy span of the Kangji Suspension Bridge. These days, it’s almost entirely residential (most of the town’s Atayal population lives over here), but it retains a few historic touches, including an old well and water pump and the terracotta tiling on the walkways.

Xiangtian Lake

Xiangtian Lake (Saisiyat name, Rareme:an) is a 25min drive away from Nanzhuang Old Street. We left the town via Miaoli Township Road 21, then turned right onto a winding, forest-lined roadway that heads uphill and dead-ends at a basin lake surrounded on three sides by green slopes. Cradled within this natural amphitheater is an open grassy area where the Saisiyat tribe hold their most important ceremonies, the Museum of Saisiyat Folklore introducing indigenous culture, and a lane full of vendors selling snacks like barbecued meats and macaw-pepper-steeped tea eggs.

There is also one unavoidable feature that will become apparent to anyone who visits Xiangtian Lake – or other Saisiyat areas for that matter. Anyone who has spent time traveling throughout Asia will likely already have come across a swastika or two adorning Buddhist temples and artworks, but that’s nothing compared to what is on display at Xiangtian Lake. They are everywhere. Left-facing, right-facing, square-on, or tilted diamond-wise. They’re on the bus stop and the toilets, they adorn the museum’s display cases, and they’ve been worked into railing metalwork and embroidered garments. And to add an extra frisson, the predominant color scheme used by the Saisiyat is red, black, and white. Traveling as we were, in a group that included a Brit and a German, it presented quite the talking point. Why would this be the case? Well, it transpires that to the Saisiyat, the shape resembles interlocking lightning bolts and is used to represent the relationship between a Saisiyat warrior and Wauan – the goddess credited with teaching the tribe weaving and farming techniques.

Curious artwork aside, a visit to Xiangtian Lake can fill up a pleasant morning – or more. A gentle path encircles the water. At just over a kilometer in length, the journey won’t take long, but you could pause for drinks at the lakeside coffee shop, grab a quick snack from one of the market stalls (many only open on weekends), and learn about the tribe from the museum’s bilingual displays (admission is NT$30). If looking for something requiring a little more energy, the lake is also the starting point of the Mt. Xiangtianhu Trail – a fabulous 10km trek through misty cedar forests.

Heading back down from Xiangtian Lake, turning right instead of left onto Miaoli Township Road 21 will take you deeper into the hills towards the start of another well-known Miaoli peak, Mt. Jiali, and even if you have no time for a serious hike, it’s well worth undertaking a brief diversion to enjoy a couple of the sights.

The road meanders through a countryside that teeters between pretty and dramatic. We passed Shibi Tribal Village (indigenous name, Raysinay), a small Atayal settlement perched on the banks of the Dadong River. Named for the tall cliffs that flank the road, the band is small, with many residents having migrated downstream to nearby Donghe due to risks posed by seasonal storms – mild in winter’s dry season, the waterway swells to a destructive torrent and temporary waterfalls gush forth from the sheer rockface during the rainy season in summer.

We made a final stop just short of Luchang Tribal Village, where the Luhu and Fengmei creeks converge to form the Dadong River. Here, a short trail leads steeply down to a platform overlooking the confluence – a spot deemed so beautiful that is called Shenxian Valley (“Valley of the Gods”), or Fairy Waterfall. At the time of writing, the suspension bridge spanning the gorge was closed for maintenance, meaning the view was somewhat obscured, but if you dine in the restaurant at the top of the steps you can enjoy home-cooked indigenous dishes as you watch water cascade down the elegant tiered waterfall.